Beauty of Persian calligraphy endless

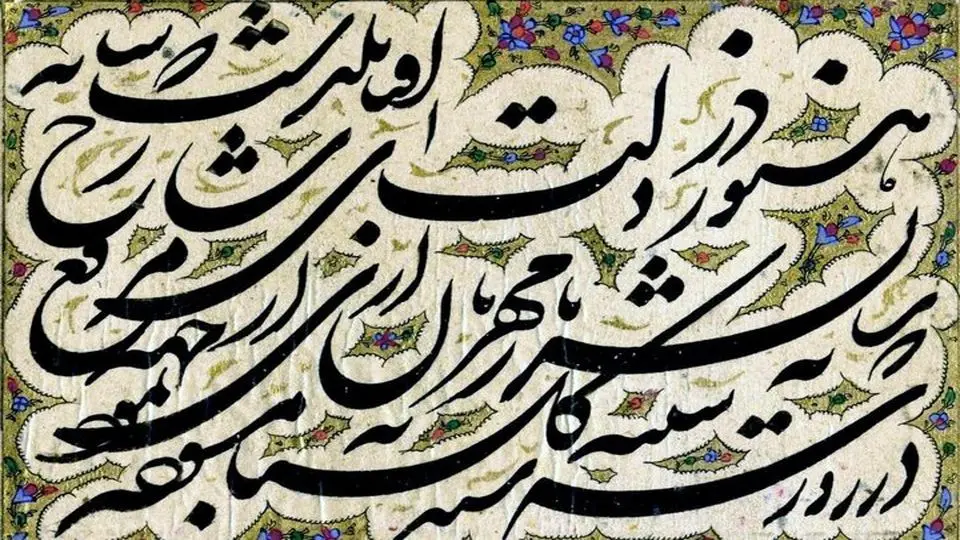

Nastaliq, bride of the calligraphy scripts, which is the combination of two pre-existing styles of calligraphy namely naskh and ta’liq matches perfectly with Persian and enjoys endless beauty.

MEHR: Nastaliq, bride of the calligraphy scripts, which is the combination of two pre-existing styles of calligraphy namely naskh and ta’liq matches perfectly with Persian and enjoys endless beauty.

The Persian word for calligraphy is "khoshnevisi" and a calligrapher is known as "khoshnevis". Calligraphy is also synonymous with khat (literally, line or script) and khat neveshtan (writing script).

The history of Persian calligraphy dates back to 500-600 BC during the first Persian empire, the Achaemenid dynasty when the original cuneiform scripts were used in monument inscriptions for the Achaemenid kings.

Around roughly one thousand years ago, six genres of Iranian calligraphy (Tahqiq, Reyhan, Sols, Naskh, Toqi, and Reqa) were created.

These genres were common for a few centuries in Persia. In the 12th century, the Naskh and Reqah styles were combined and a new genre of Persian calligraphy named Ta’liq (Taliq) was invented.

Eventually, in the 14th century, Naskh and Taliq were combined, and the most attractive Persian calligraphy style, Nasta’liq was created.

Mir Emad Hassani (1554 -1615) known to orientalists as Mir Emad is perhaps the most celebrated Persian calligrapher. It is believed that the Nasta'ligh style reached its highest elegance in Mir Emad's works. Other notable figures include Mirza Asadollah Shirazi, Mirza Gholamreza Esfehani and Mirza Mohammadreza Kalhor of the Qajar Period.

UNESCO selected Iran’s national program to safeguard the traditional art of calligraphy on its Register of Good Safeguarding Practices in 2021.

The tradition of calligraphy has always been associated with the act of writing in Iran, and even when the writers had limited literacy, calligraphy and writing were still intricately linked.

With the advent of printing and the emergence of computer programmes and digital fonts, this art gradually declined and the emphasis on pure readability replaced the observance of both readability and aesthetics. This resulted in a decline in the appreciation of calligraphy among the new generations.

The safeguarding of the Iranian calligraphic tradition thus became a major concern in the 1980s.

Iran’s national program to safeguard the traditional art of calligraphy aims to expand informal and formal public training in calligraphy, publish books and pamphlets, hold art exhibitions, and develop academic curricula, while promoting appropriate use of the calligraphic tradition in line with modern living conditions.

Some of the work on this programme was started by the Iranian Calligraphers Association before the 1980s, and given its immense popularity, the public sector turned it into a national programme by redefining and coordinating it on a large scale based on the experiences of the public and private sectors.

Iranian women calligraphers have also contributed to the history of Persian calligraphy, particularly Mir Emad's daughter Goharshad who was trained by her father. Many women in the Qajar courts were experts in the art of calligraphy, including Fakhrodolleh (Touran Aghaa) who was a Qajar princess and the daughter of Nasereddin Shah. Many of these princesses have also inscribed copies of the Holy Quran.

Calligrapher and poet Mir Ali Tabrizi who lived during the 14th century is often credited with the invention of nastaliq, Iranica wrote. But despite Mir Ali’s fame, the sole known extant manuscript by his own hand appears to be a copy of Persian poet Nezami’s Kosrow o Shirin now at the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington.

Jafar Tabrizi, who identified his teacher as Mir Ali bin Hassan Tabrizi, a contemporary of Mir Ali Tabrizi, wrote in a style closely analogous to that of Mir Ali as did his contemporary Az’har Soltani.

Jafar Tabrizi, also known as Baysonqori, not only considered Mir Ali as the inventor of nastaliq, but also claimed that the latter was skilled in “all styles of writing,” adding that both his calligraphy and his verse were notable for their equilibrium.

Mirza Mohammad-Hossein Seifi Qazvini was known by the nickname Emad al-Kottab (Pillar of the Calligraphers).

Calligrapher Yadollah Kaboli Khansari revived and promoted shekasteh nastaliq, a style of Persian calligraphy.

Renowned 19th century master calligrapher of nastaliq style Mohammad Hussein Shirazi is known as ‘Kateb-ol-Sultan’ (calligrapher of the king). He was famous for his command of various variations in nastaliq script, a cursive style in Persian calligraphy with long horizontal strokes and short verticals.

In 2017, calligraphy master Gholamhossein Amirkhani awarded by French embassy in Tehran the highest order of the country Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur.

French ambassador to Tehran François Sénémaud praised Amirkhani as Iran’s cultural ambassador; “your name is entwined with Iranian Calligraphers Association (ICA); your fame and star descended when you trained many disciples and when your beautiful lines adorned the papers of art during three score years; you have been pivotal to shining of Iranian and Persian literature and culture in the world; your calligraphy of towering figures of Persian literature as Hafiz, Saadi, etc., served thy country well”.

Amirkhani was selected as a Living Human Treasure in Iran on February 18, 2020.

The 83-year-old calligrapher, who is the director of the Iran Calligraphers Association, is one of the few Persian calligraphers who has shown great skill in nastaliq. Numerous calligraphers consider him as the best living calligrapher of this style.

Computerized calligraphy is also a relatively new trend. The "IranNastaliq" font can be installed on Microsoft Word.

Calligraphic prints on fabric, particularly T-shirts are currently a popular trend.

The post-Islamic Iranian architecture is rich with surfaces that are harmoniously decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy. Scripts in various patterns and colors are used in the tilework of Iranian architecture.

In Iran, people of different age groups (from 7 to 70 plus years) and from different walks of life attend calligraphy courses.